Story of Ménerbes

The origins.

The origins.

The name of Ménerbes would be derived from that of the Roman goddess Minerva but this hypothesis remains to be verified. In 1081, the texts refer to the village under the name of Menerba and subsequently of Minerbium. In Provencal, the village is called Menèrba or Menerbo. The official foundation of the village dates from the 11th century, but many vestiges show a much older occupation dating back to antiquity and prehistoric times. The first significant signs of human occupation on the territory of Ménerbes were unearthed in the "Soubeyras" rock shelter and date back to the Upper Paleolithic, some 35,000 years ago. The Pitchoune dolmen located below the village attests to the presence in the Neolithic period (around 4000 BC) of organized communities. This presence extended elsewhere in the countryside, including in the Soubeyras shelter, as well as on the rocky outcrop that bears the present village.

Roman Empire.

Roman Empire.

The Domitian Way (118 BC), a major axis connecting Italy to Spain, ran north of the town. A roadhouse called Ad Fines placed between the cities of Cabelio (Cavaillon) and Apta Julia (Apt) was undoubtedly located in the territory of Ménerbes. The lands of the town have yielded many vestiges indicating a Roman presence from the 1st century. av. JC: an Ionic column capital discovered in 1986 on the banks of the Calavon which seems to be the trace of an important monument, for worship or funeral, the remains of a potter's workshop specializing in the manufacture of utility pieces (amphoras, flat tiles) in the Bas-Eyrauds / Artèmes district, an altar to Silvain offered by Sextus Iulius Bellatulus and Gaius Iulius Marcellinus (Guimberts district), a stele dedicated to Flavia, daughter of Graecinus (Saint-Alban district).

Late antiquity.

Late antiquity.

During the collapse of the Roman Empire, the end of the great cities, places of power, benefited the campaigns which saw the populations taking refuge there for purposes of survival. The installations and precarious habitats built during this period have left few traces but some are still visible in Ménerbes: the funeral site of Saint-Estève (end of the 4th century), the cave installations of the abbey of Saint -Hilaire, in many houses such as Maison Dora Maar, arrangements dug in the molasse (housing funds, silos, vats, beam holes ...), along the path leading to the Porte Saint-Sauveur, the rocky escarpments pierced with holes for housing beams and various arrangements bear witness to houses whose stone and wooden overhangs have now disappeared.

Religious life in the 5th c. and the legend of Castor of Apt, says Saint Castor.

Originally from Nîmes, he founded a monastery in a place called Manancha, the location of which remains mysterious but which, according to some, could be in the territory of Ménerbes.

Around 410, on the death of the bishop of Apt, the clergy and the population of this city came to ask Castor to entrust him with the episcopal see. He refused and took refuge in a cave in the Luberon, perhaps in the district of Ménerbes known as San Castro. The aptésiens eventually found him and had him consecrated bishop. Several miracles are attributed to him; He is said to have made his way to his monastery from Apt on a stormy night without his clothes getting wet.

The feudal castrum.

The feudal castrum.

After several centuries of disorganization, space and territory have been restructured around the castrum, a veritable entity placed under the authority of co-lords, themselves attached to a centralized power.

Perched on a rocky outcrop, the village ensured its defense by extending the naturally vertical walls with ramparts punctuated with towers and arches of which few traces remain today. Within these defenses, a dense network of precarious dwellings and narrow alleys rubbed shoulders with the quality buildings of the co-lords and wealthy residents.

One of the rare medieval vestiges remains in the north-eastern facade of a building which would later be occupied by the hospital and which is visible from outside the village. It is a twin bay dating from the end of the 12th century. or the first half of the 13th century. which is the oldest bay identified to date in the village.

Saint-Hilaire abbey.

Saint-Hilaire abbey.

(or more precisely the Carmelite convent of Saint-Hilaire), built in the 13th century, preserves important traces of the Middle Ages in the cloister and the chapel. The late Romanesque sacristy and a side chapel from the 14th century. open onto the single nave, the pointed barrel vaulting of which is indicative of the 13th century Gothic period. The walls retain vestiges of frescoes dating from the end of the Middle Ages.

Leave the middle ages.

Leave the middle ages.

The end of the Middle Ages was marked by the "great plague" or "black plague" which decimated the population of the Luberon in 1348. The village was partly deserted but it found a new impetus illustrated by the development of new neighborhoods outside ramparts. The oldest cadastre in the town, established in 1414, lists the Place de l'Oulme and the Saint-Estève district.

The construction around 1510 of the parish church, replacing the former Saint-Sauveur priory, is the most flagrant manifestation of this renewal and of the society's ability to recover from the horrors of the Middle Ages.

The wars of religion: five years of siege (1573 - 1578)

The wars of religion: five years of siege (1573 - 1578)

The Vaudois came from the lower alpine valleys at the end of the 15th century. repopulated Provence after the great plague. They revived the economy, cultivated the wasteland and rebuilt farms, villages and castles. Their beliefs and their religious practices are considered heretical, they officially become Protestants in 1532 and are condemned by the so-called “de Mérindol” judgment in 1540. In 1545, by order of François I, the French troops led by Baron Maynier d 'Oppède helped by the pontifical power of Avignon engage in massacres against this community.

In this context of wars of religion, the kingdom of France and Provence are set ablaze.

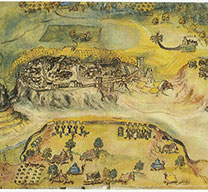

After the Saint-Barthélemy massacre (August 24, 1572), the Protestant leaders decided to make an example. Ménerbes, who had particularly distinguished himself by his loyalty to the Pope during the beginning of the wars of religion, was invested on October 4, 1573 by about 150 armed men led by Scipio de Valavoire and religionists from Valmasque. The Protestants take control of the place and reinforce the fortifications.

This outrage against a city dependent on the Holy See triggers a general mobilization. A seat was installed under the command of Henri d´Angoulême, son of King Henri II, Grand Prior of France and Governor of Provence. At his side are Albert de Gondi, Marshal de Retz as well as Dominique Grimaldi, new rector of Comtat Venaissin and Saporoso, pontifical captain who commands companies from Corsica and Italy, that is in all 15,000 men. After the troops were installed at the foot of the village, the eagle's nest was surrounded by trenches, redoubts, forts and gun batteries.

Outnumbered and poorly armed, the besieged managed to defend their position for five years, with the help of Huguenots from Mérindol, Aix, Cavaillon and Arles. Under the leadership of Rector Grimaldi and the papal orders, between September and October 1577, Le Castellet received 907 cannon shots, or 14 tons of scrap. These cannonades, which caused fires and numerous destructions, including that of the Cornille Tower, were followed by interminable transactions. Harassed, deprived of drinking water and trapped in their destroyed fortifications, the Protestants accepted the surrender on December 9, 1578. The 120 soldiers who still held the place left the village, banners displayed and drums beating, and retired to Murs. Ménerbes comes out of this terrible episode, one of the most memorable of the religious wars in Provence.

Resilience.

Resilience.

Deeply traumatized by the period of the siege, the village rebuilt its defenses, equipped itself with new gates, a drawbridge and a fortress-like building, the Citadel, which served as a garrison and then as the governor's palace.

Some doors are associated with a chapel. This grouping which mixes spirituality and defense takes on symbolic importance by affirming, after the siege, the power of the triumphant Catholic religion. In ruins after the siege, the parish church (which would later become the Church of Saint-Luc) was restored. A new bell tower resembling a defense tower was built in 1594 and a new bell was installed to warn of any threat.

The common house is rebuilt on the site of a former guardhouse. It is flanked by a tower known as the "clock tower", built between 1610 and 1613 and probably capped from the beginning with a campanile and a bell. This building, which is still very significant in the village today, represents from its construction a strong symbol of power.

After being occupied by besieging armies, the surrounding countryside is in a state of devastation and neglect. From the 1580s, we witnessed a restructuring of the terroir with the multiplication of new agricultural bastides in the plain under the aegis of notables having a residence in Ménerbes. These stately bastides and the farms of the small owners punctuate the landscape. In this reorganization of agricultural space into large lands and terraces, dry stone construction is developing.

17th and 18th centuries : the resorts.

17th and 18th centuries : the resorts.

Away from the royal territory, the Comtat Venaissin retains ancient privileges. Protected by its papal administration, it is not subject to the taxes which weigh heavily on the king's subjects. These conditions favor the development of the economy and the establishment of large landowners.

The village which preserves its old walls and its old residences inherited from the Middle Ages, knows in the XVIIth and XVIIIth century. major transformations: relocation of the old hospital, reorganization of the old town house, construction of the new portal, reconstruction of the chapels of Notre-Dame des Grâces and Saint-Blaise.

Most of the mansions that we can still admire today such as the Hôtel d'Astier de Montfaucon, the Hôtel de Carmejane, the Castellet, the Hôtel des de Ferres (now Maison Dora Maar), the Hôtel de Tingry and the Hôtel de Girardet de Castelas were built or transformed during the 17th-18th century. These aristocratic holiday residences, built in the heart of the village, have large interior spaces and terraces and pleasure gardens opening onto the landscape.

The town's coat of arms, which is an 18th century creation, symbolizes the forces involved. The municipality is represented by the monogram MB surrounded by two crescents, signs of nobility, wealth and growth, which glorify the municipal power of the consuls. The two keys above represent the pontifical power entrusted to the legates. The ensemble is dominated by a stylized representation of the ramparts and towers of the village.

After the revolution of 1789, Ménerbes remained faithful to Pope Pius VI. The municipal council will not celebrate the attachment to the French Empire until November 1, 1791, two months after the restitution of Avignon and the Comtat Venaissin to France.

XIXth century : peasants and craftsmen.

XIXth century : peasants and craftsmen.

With omnipresent viticulture alongside cereal, fruit and market gardening production, silkworm breeding became in the 19th century. one of the specialties of the region. Sericulture is often a side activity: the cocoons are produced by families who dedicate part of their farm or even their home to them. However, a more industrial production is set up: the silk is treated on the spot in a silkworm and a spinning mill.

The exploitation of stone quarries, including the white limestone known as "Pierre de Ménerbes", has been a part of economic activity since the 19th century. Beyond the extraction and the substantial income it brought, this activity had a direct impact on the municipality with the creation of quarters reserved for quarrymen and roads reserved for the movement of convoys loaded with blocks of stone.

In the village, few monuments or spectacular residences were built during this period of transition marked by the simplicity of the residents who were often peasants, agricultural workers or artisans and traders living in simple houses. We are busy maintaining the building, repairing facades without frills, redoing or creating openings, redoing the lime plaster. Some houses have a bread oven, an oil mill or sundials.

XXth century : artists and writers.

From the "Trente Glorieuses", many artists settled in Ménerbes. From Nicolas de Staël to Dora Maar and Georges de Pogédaïeff, passing by Joe Downing, Jane Eakin or even Antonin Barthélemy ... and writers like François Nourissier and Peter Mayle ... This generation of artists contributes to the reputation of the site which, with the development of tourism and the installation of new residents, promotes the renovation of the built heritage in the village and in the countryside. Strong competition from large industrial centers and the appearance of synthetic fibers, the silk craft industry has gradually disappeared. But agriculture remains an important activity of the municipality, especially viticulture and fruit production.